The office experiment: Can science build the perfect workspace?

Windows, desks and employees are being wired up in a quest to create healthy, evidence-based environments.

In late May, eight employees of Mayo Clinic's medical-records department packed up their belongings, powered down their computers and moved into a brand new office space in the heart of Rochester, Minnesota. There, they made themselves at home — hanging up Walt Disney World calendars, arranging their framed dog photos and settling back into the daily rhythms of office life.

Then, researchers started messing with them. They cranked the thermostat up — and then down. They changed the colour temperature of the overhead lights and the tint of the large, glass windows. They played irritating office sounds through speakers embedded in the ceilings: a ringing phone, the clack of computer keys, a male voice saying, “medical records”, as if answering the phone.

On a warm morning in June, the recording is playing on a loop. “I've timed it,” says Randy Mouchka, one of the relocated office workers, with exasperation. “It's 55 seconds.” Today, the air feels stale and stuffy, but the sun is streaming in — an improvement over last week, Mouchka says, when the researchers kept the window shades pulled all the way down.

These people are the first guinea pigs in the Well Living Lab, an immersive, high-tech facility where Big Brother meets big data. The lab — a collaboration between Mayo Clinic in Rochester and Delos, a design and technology firm based in New York City — was built to host studies on how the indoor environment influences health, well-being and performance, from stress to sleep quality, physical fitness to productivity.

LISTEN

Brent Bauer explains the idea behind his massively malleable living space.

Down the hall, in a glass-walled control centre crammed with computers, scientists are keeping a close eye on Mouchka and his colleagues. “We have a panoramic view of everything that's happening,” says Alfred Anderson, the lab's director of technology. One monitor features a live video feed; others display light levels, air temperature, humidity and atmospheric pressure from the 100 or so sensors scattered around the office. The workers are wired up, too: a large monitor reveals the readouts from biometric wristbands that measure their heart-rate variability and the electrical conductance of their skin, both crude measures of stress. Researchers will monitor all of this as they subject the employees to nine different types of office environment. “We're in 'Bad Office 2' today,” Anderson says.

Experts know that indoor spaces can pose health risks. Excessive noise is thought to contribute to high blood pressure and heart disease. Artificial light can disrupt circadian rhythms and may increase the risk of certain cancers. There is growing evidence that a sedentary lifestyle could damage health, leading to type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer or early death — a major concern when so many modern jobs demand sitting at a desk all day. And workplace stress is thought to cost hundreds of billions of dollars worldwide each year in sick days, health-care costs and lost productivity. “We spend 90% of our time indoors,” says Brent Bauer, the Well Living Lab's medical director. “If we don't optimize that, we're going to have a hard time optimizing wellness as a whole.”

Scientists hope that the lab will allow them to add to the growing literature on the impact of the built environment, and to produce practical, evidence-based recommendations for creating healthier indoor spaces ranging from offices to homes. It's an ambitious mission that will involve integrating and interpreting vast quantities of data. But scientists, companies and organizations — impressed by the lab's size, scope and approach — are eager to see what it finds. “Everybody I've talked to who has heard about it is very excited because it is truly unique,” says Gail Brager, associate director of the Center for the Built Environment at the University of California, Berkeley.

Living in the lab

Decades of research have revealed that indoor spaces can affect how people think, feel and behave. In a landmark 1984 study1, Roger Ulrich, a pioneer in health-care design research now at Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg, Sweden, found that people recovering from surgery in hospital rooms with views of nature needed shorter stays and fewer doses of strong pain medication than did those in rooms looking onto a brick wall. Others have reported that certain kinds of artificial light can improve sleep and reduce depression and agitation in people with Alzheimer's disease2; that higher air temperatures seem to curb calorie consumption3; that employees take more sick leave when they work in open-plan offices4; and that children in daylight-drenched classrooms progress faster in maths and reading than do those in darker ones5.

In 2012, the accumulating research led Delos — which aims to create spaces that boost health and wellness — to start developing evidence-based guidelines for healthier buildings. The WELL Building Standard, first released in 2014, outlines more than 100 best practices, from using paints that release minimal levels of potentially toxic compounds to organizing cafeterias so that they prominently display fruit and vegetables. Buildings that meet enough of the standards can become 'WELL Certified', in much the same way that buildings can earn sustainable, eco-friendly certification.

But in developing the standard, Delos noticed gaps in the scientific literature. There were many studies on a single aspect of the indoor environment, such as light or sound, but in the real world, these variables operate in concert. Studies have shown, for example, that as the temperature and humidity of indoor air increases, its perceived quality declines6. Programmes to reduce indoor air pollution could yield greater benefits if building managers pay attention to these other factors.

Ackerman + Gruber for Nature

In the Well Living Lab's control room, researchers track dozens of variables, including lighting, temperature, humidity and noise levels.

Other recommended practices might conflict. In June, researchers reported7 that office workers scored higher on tests of cognitive function when the room was better ventilated, but many studies have found that background noise impairs cognitive performance. What if increasing air flow requires office workers to open a window onto a loud street? If one worker wants quiet, and another wants fresh air, can evidence decide who should win?

“There are some building-science labs out there who try to bring in as many components as possible, but we never thought they got to the point where they really could address all the issues that might come up in a building design standard,” says Dana Pillai, president of Delos's research division and executive director of the Well Living Lab. “So we thought we'll just do it ourselves.” In 2013, Delos began discussions with Mayo Clinic. Together, the organizations decided to build an adaptable, immersive lab that gave them precise control over many environmental variables and mirrored the real world as closely as possible.

They assembled an 18-person team and sketched out a 700-square-metre dream lab. The facility, which cost more than US$5 million to build and occupies the third floor of an office building, is endlessly transmutable. The tint of the windows can be altered with a mobile app; LED lighting can be tuned to different colours and intensities, and the motorized shades can be programmed to rise and fall at specific times of day. “We can move walls, we can move plumbing, we can move ducts,” says Bauer. Researchers can transform the lab from a large, open-plan office to a cluster of 6 apartments or 12 hotel rooms, where study participants might live for weeks or even months. “It's imaginative,” says Alexi Marmot, an architect and researcher at University College London. “This really has potential to allow all sorts of things to be done that we have not been able to do.”

The Well Living Lab occupies a scientific sweet spot — more controlled than the real offices used for field studies and more realistic than many laboratories. “That they're going to have people there for extended periods of time, I think is really important,” says Brager, who was not involved in the planning or design of the lab, but will serve on its scientific advisory board. “While this still isn't quite a real building — so there's still going to be some question about the ability to generalize to real-world conditions — it's a lot closer than the conventional labs.”

Office space

The Well Living Lab's scientists are starting small and simple, drawing on previous findings to create a variety of office environments that they hypothesize will have positive, negative or no effects on workers' comfort and stress. They are monitoring participants' responses to these changing conditions with daily surveys — which ask for ratings of comfort, satisfaction, productivity and stress — and the biometric wristbands. This study is a trial run, designed to validate the lab's systems and approach, as well as the basic idea that office conditions influence employees' well-being.

Later this year, the team will explore in more detail how light, noise and temperature affect employee performance, as measured by tests of executive function and productivity, surveys of perceived productivity and physiological measures. Crucially, the researchers will also assess how variables interact, which have the greatest impact on individual and group performance, and what the cumulative effects of changing them are. Such studies might eventually show, for example, that an office with plenty of natural light, a thermostat set to 21 °C and a modest hum of background noise produces the happiest employees, who respond to e-mails quickly or enter database information accurately.

Ackerman + Gruber for Nature

Dozens of environmental sensors are placed throughout the office.

“The world is a multicomponent place, so there's a benefit of doing that — that's how the real world is,” says Mariana Figueiro, who directs the Light and Health Program at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York. But there's a danger, too, she says. “Those are probably going to be very expensive studies, and they might be very noisy” statistically, which may make the data difficult to interpret.

Even the relatively simple pilot study is already generating nearly 9 gigabytes of data per week. As the researchers enrol bigger groups and monitor more variables and outcomes, that figure could expand tenfold.

The complexity will also grow as the team begins to layer studies on top of one another. Nicholas Clements, a director at Delos Labs, is collecting samples of the office microbiome: bacteria, fungi and more that live in the office's nooks and crannies, and on the surfaces that people touch every day. Scientists think that it may be possible to actively shape the indoor microbiome to improve human health, but research into this idea is in its infancy.

“We'd like to push that science further and hopefully we can accomplish that here,” says Clements, who plans to test whether certain environmental interventions, such as changing flooring and surface materials or installing a 'green wall' of living plants, can alter the office's microbes — or the health of its human occupants. (He will also track participants' exposure to indoor air pollutants, such as the volatile organic compounds emitted by paint and furniture.)

Other Mayo faculty members are eager to use the facility. Early next year, ergonomist Susan Hallbeck will investigate whether standing desks improve health in workers with and without certain risk factors for disease — and, if so, what the optimal ratio and schedule of standing and sitting is. Research has shown that using a standing desk can slightly increase the number of calories burnt, but the evidence for broader health benefits is limited. “This is a dream study,” says Hallbeck.

In addition to the office space, the lab currently contains a single studio apartment, which the researchers will use to learn how to design living spaces that improve sleep quantity and quality in night-shift workers, and whether changes in these workers' circadian cycles influence their microbiota.

And whenever the scientists get together, they start churning out new ideas and hypotheses. Perhaps they could turn the space into a classroom, study whether lighting can reduce falls among older people or probe whether certain office conditions make it easier for people with traumatic brain injuries to return to work.

“We're taking kind of a kid-in-a-candy-store approach,” Bauer says. “We've got almost endless opportunities now to start answering these important questions about, 'How do we optimize the indoor environment?'”

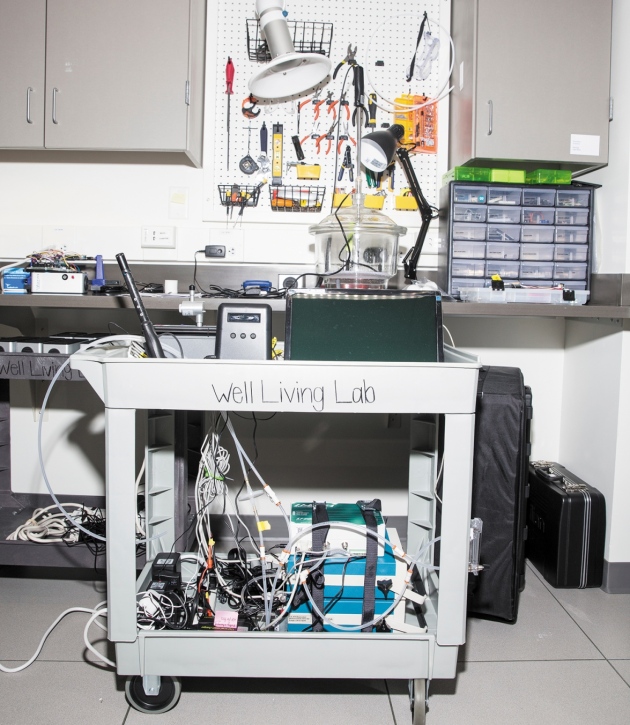

Ackerman + Gruber for Nature

Tools in the Hardware Development Lab, allow researchers to reconfigure the office space into apartments, hotel rooms and more.

Complex challenges

The lab's leaders still have a long wish list of sensors and technologies that they would like to deploy, and they're eyeing international expansion. They're not alone. A handful of other teams are taking an immersive, multivariable approach to studying human responses to indoor conditions, using flexible facilities — from the Total Indoor Environmental Quality Lab at Syracuse University in New York, to the SenseLab at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, which should open in December.

But big ambitions can be expensive. To help cover costs, Mayo and Delos have been recruiting corporations and other organizations to the Well Living Lab Alliance. Members make contributions ranging from $75,000 to $300,000, and receive several benefits in return, including early access to research findings, attendance at an annual Well Living Lab summit and discounts on sponsored research. So far, nine organizations — in industries including construction, property management, health-care technology, manufacturing and computing — have signed up.

Corporate partnerships aren't unusual in built-environment research, but scientists say that the lab will have to select its members carefully, be transparent about funding sources and work to ensure scientific independence. “In this field that's normally been neglected, there's now somebody who clearly has very deep pockets,” Marmot says. “I think it's all to the good. But let's make sure that the appropriate scientific review processes are there.”

Bauer says that all proposed studies — including those sponsored by alliance members — will need approval from the lab's leaders, its joint steering committee and Mayo's institutional review board. “I think we've been very clear with the companies that are participating that membership isn't a carte blanche,” he says.

At the Well Living Lab, the workers are now feeling at home. Despite being poked, prodded and observed by the scientists behind the glass, the first test participants love their temporary office. The desks are adjustable, the chairs comfy and the windows big. Even the air, they say, seems cleaner than in their old offices, to which they will eventually return. “I don't want to go back,” says Mouchka. “I'm hoping we're here for a year.”

Latest from Redaction web 2

- Lien du ministère de la santé

- Annonce du dépôt des dossiers des participants au Salon Du Livre Universitaire Scientifique et Technique pour L’année Universitaire 2019/2020 de l'Université des Frères Mentouri Constantine 1

- Programmes des bourses BID

- Initiative Prima lancement d'un programme de stages aux jeune chercheurs pour l'année 2020/2021

- Troisième appel à projets Algéro-Espagnol sera lancé à partir du 01 /04 /2020 au 01/06/2020