هيئــات لمتابعــة الإدمــاج المهنــي لخريجــي جامعــة منتــوري

سخرت جامعة الإخوة منتوري بقسنطينة، العديد من الهيئات لمتابعة و تسيير الإدماج المهني للطلبة المتخرجين بخصوص خلق مؤسسات استثمارية، و ذلك بهدف إنجاح التكامل بين الجامعة و القطاعين الاقتصادي و الاجتماعي، و كذا المحافظة على التواصل بين القطبين.

و حسب ما ورد في بيان من رئاسة الجامعة، فإن الأخيرة التزمت منذ عدة سنوات بدفع الإدماج المهني للطلبة المتخرجين كاهتمام أساسي من خلال وضع عدة أجهزة لإبقاء التواصل مع القطاع الاقتصادي و الاجتماعي، و هي علاقة يمكن أن تتحقق، يضيف البيان، بتنظيم التعليم في المجال المؤسساتي بحيث يصبح التكوين الذي يزاوله الطالب في المؤسسة عنصرا أساسيا يسمح بالإدماج المهني، إضافة إلى برمجة أكبر عدد من المتخرجين في نهاية الدورة سواء في شهادة الليسانس أو الماستر، بتأطير مختلط بين الأكاديميين و المهنيين في إطار العقود المبرمة ما بين جامعة الإخوة منتوري و الشركات الاقتصادية و الاجتماعية، و كذا إقحام المهنيين في مختلف التكوينات في شهادة ليسانس أو ماستر خاصة في الدورات المهنية، مع مساهمة الشريك الاقتصادي في هيئات المحلفين لتقييم مذكرات التخرج.

كما سمحت الإجراءات المتخذة بوصول المعلومة خاصة في مجال اللقاءات بين المعاهد و المؤسسات المعنية بالعمالة، و إدماج وضع "الطالب صاحب المؤسسة" مع ضمان مرافقة دار المقاولاتية لمدة سنة، و هي عملية ترتكز على عدة محاور لإنجاح الإدماج المهني للمتخرجين في القطاعين الاقتصادي و الاجتماعي، أولها الترويج و التسويق للتكوين المقترح من طرف الجامعة، و كذا مرافقة المتخرجين لوضع السير الذاتية عن طريق مركز المسارات المهنية، إضافة إلى دعم و رعاية المؤسسات و تحضير الطلبة لاقتحام عالم الشغل من خلال مختلف المشاريع المهنية، مع اقتراح حلول مبتكرة للشركة المستهدفة.

كما ورد في ذات البيان، أنه قد تم إقحام البحث الجامعي لتحقيق الاندماج مع القطاعين الاقتصادي و الاجتماعي، من خلال تقوية قدرات الجامعة في ما يخص آداءات الخدمات في الدراسة و البحث و الخبرة و تحويل الأطروحات إلى مؤسسات فعلية و تمويلها، و كذا تثمين نتائج البحث و وضع المعدات اللازمة، كما سخرت الجامعة هياكل نشطة لتسيير و متابعة الإدماج المهني للمتخرجين، كمكتب الربط بين الجامعة و المؤسسة المكلف بتنظيم متابعة التربصات، دار المقاولاتية لخلق المؤسسات، و كذا مركز المسارات المهنية المخصص للتوظيف و النادي الجامعي.

خ/ض

Colloque international sur le plurilinguisme: Nécessité de «dépassionner le débat»

« L'Algérie est un pays riche en langues, un pays riche en cultures et en tant que chercheurs on se doit de réfléchir sur la manière d'intégrer toutes les langues en présence dans le processus de l'enseignement apprentissage», nous a déclaré hier le professeur Cherrad Nedjma, enseignante-chercheuse à la faculté des lettres et des langues de l'Université Mentouri de Constantine à l'ouverture du colloque international sur «les dynamiques plurilingues, usages et enseignement des langues» qui se tient les 9 et 10 mai en cours dans le bloc 500 places pédagogiques de cette université. Notre interlocutrice qui fait partie du comité scientifique du colloque indiquera que ce dernier s'articule sur trois volets de recherche : l'enseignement apprentissage dans les situations plurilingues, le plurilinguisme dans le contexte social et le plurilinguisme dans le contexte institutionnel. «L'objectif a été d'abord de réunir un grand nombre de chercheurs de renommée internationale à travers le monde». Elle poursuivra en notant qu'il y a des invités de France, de Tunisie, de Turquie qui viennent partager avec une palette de chercheurs algériens des universités de Tizi-Ouzou, Batna, Mascara, Mostaganem et de Constantine, leurs différentes approches des situations plurilingues, «afin que l'on puisse étudier ce phénomène en dépassionnant le débat. La langue étant véhicule de l'identité, de la culture parfois, il nous est trop compliqué, en tant que locuteurs, d'objectiver l'objet langue à enseigner, autrement dit de le rendre comme étant un objet qu'on peut examiner comme on examine un malade». En somme, l'objectif est d'étudier le rôle du plurilinguisme dans l'enseignement apprentissage des langues, comment intégrer les langues dans le cursus scolaire, quelles sont les politiques linguistiques et éducatives mises en œuvre, comment est-ce qu'on peut les évaluer et comment on peut rendre cet enseignement apprentissage plus pertinent.

«Nous n'avons pas la prétention d'apporter des solutions, mais au moins d'avoir des résultats, des approches qui pourraient permettre aux enseignants et chercheurs d'améliorer l'enseignement apprentissage, notamment. Dalila Morsly, professeur émérite à la retraite de l'université d'Angers (France) mais qui fait toujours partie du laboratoire sciences du langage, analyse des discours didactiques (SLADD) de l'université de Constantine, et a enseigné souvent à l'université Mentouri, participe au colloque par une communication sur «les petites annonces de la presse algérienne». Elle dira à ce propos : «J'ai présenté un travail que j'ai effectué sur la presse pour montrer le fonctionnement du plurilinguisme dans la presse et en particulier dans les petites annonces.

J'ai constaté que dans les petites annonces comme dans de nombreuses autres rubriques de journaux algériens, qu'ils soient de langue française ou arabe, il y avait souvent plusieurs langues qui apparaissaient, des langues en contact. Et je m'intéresse à la façon dont les langues différentes apparaissent dans la rubrique des petites annonces, en particulier dans les offres d'emploi, pour essayer de comprendre quel est le rôle des langues dans les propositions d'offre d'emploi dans la société algérienne».

Concours d'accès aux écoles nationales supérieures

*Si vous êtes parmi les meilleurs titulaires des deux premières années de licence

** Si vous n’avez pas redoublé.

*** Si vous êtes titulaires du Bac 2013 (L3) ou 2014 (L2).

Les dossiers doivent être déposés à la direction des études des écoles préparatoires de la région selon les tableaux suivants ou au niveau des vice-rectorats des universités qui les transmettront aux écoles correspondantes dans les tableaux suivants Date limite de dépôt ou d’acheminement au niveau des écoles: le 31 mai 2016.

PROGRAMME LICENCE BIOINFORMATIQUE

Mille milliards d'espèces biologiques vivent sur terre

WASHINGTON - La Terre pourrait abriter près de mille milliards d'espèces dont seulement 0,001% serait aujourd'hui identifié selon une étude américaine publiée lundi.

Publiée par la revue américaine Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (Comptes-rendus de l'Académie américaine des Sciences), l'estimation repose sur des données représentant plus de 5,6 millions d'espèces microscopiques et non-microscopiques évoluant dans 35 000 lieux, dans tous les océans et sur tous les continents du monde, à l'exception de l'Antarctique.

"Estimer le nombre d'espèces vivant sur la Terre est l'un des plus grands défis de la biologie,'' a indiqué l'auteur principal, professeur associé à l'université de l'Indiana, Jay Lennon,'' dans un communiqué. ''Notre étude apparie les plus grands ensembles de données disponibles avec des modèles écologiques et de nouvelles règles écologiques expliquant pourquoi la biodiversité est synonyme de profusion. Cela nous a permis d'obtenir une estimation nouvelle et rigoureuse du nombre d'espèces microbiennes présentes sur la Terre.''

Plusieurs tentatives précédentes, ajoute M. Lennon, avaient tout simplement ignoré les micro-organismes ou n'avaient pris en compte que des ensembles de données anciennes qui reposaient sur des techniques biaisées ou des extrapolations discutables.

Au cours de ces dernières années, la prise de conscience que les micro-organismes étaient significativement sous-échantillonnés a favorisé une explosion des efforts déployés en matière d'échantillonnage des espèces microbiennes, a dit M. Lennon.

Ces efforts ont inclus la collecte des micro-organismes du corps humain par le Projet sur le microbiome humain des Instituts nationaux de Santé des Etats-Unis, des micro-organismes marins par l'expédition Tara Oceans, et des micro-organismes aquatiques, terrestres et liés aux hôtes par le Projet sur le microbiome de la Terre.

Ces sources de données et de nombreuses autres ont été compilées afin de créer l'inventaire, dans la nouvelle étude, qui a rassemblé 20 376 procédures d'échantillonnage sur les bactéries, archées et champignons microscopiques et 14 862 procédures d'échantillonnage sur les communautés d'arbres, d'oiseaux et de mammifères.

Les résultats de l'étude ont également suggéré que parvenir à effectivement identifier chacune des espèces microbiennes présentes sur la Terre est un défi énorme qui dépasse presque l'entendement.

Par exemple, le Projet sur le microbiome de la Terre - un projet mondial multidisciplinaire visant à identifier les organismes microscopiques - n'a à ce jour répertorié qu'à peine 10 millions d'espèces.

"Parmi ces espèces classifiées, seulement environ 10 000 ont vu le jour en laboratoire, et moins de 100 000 ont des séquences répertoriées,'' explique M. Lennon. ''Nos résultats montrent que 100 000 fois plus de micro-organismes n'ont toujours pas été découverts et que 100 millions d'autres ont encore besoin d'être complètement explorés. La biodiversité microbienne est bien plus vaste, semble-t-il, que nous ne l'avons jamais imaginée".

Découverte de la presque la totalité des anomalies génétiques à l’origine des cancers du sein

PARIS – Des chercheurs ont découvert pratiquement toutes les anomalies génétiques à l’origine des cancers du sein, une « avancée majeure » qui pourrait permettre de développer de nouveaux traitements plus efficaces contre cette maladie, révèle une étude publiée mardi dans la revue britannique « Nature ».

« C’est une avancée majeure dans la compréhension des mécanismes dans nos cellules qui, lorsqu’ils sont altérés, aboutissent à des cancers du sein », souligne Christine Chomienne, directrice de recherche à l’Institut français du cancer (InCA) qui a co-dirigé l’étude avec l’Institut Sanger à Cambridge (Royaume-Uni).

Elle ajoute que l’étude a permis d’établir « un catalogue quasi exhaustif des anomalies qui interviennent dans les cancers du sein ».

Tous les cancers sont dus à des mutations qui se produisent dans l’ADN de nos cellules au cours de notre vie. Ces changements interviennent à cause de l’environnement mais également au fur et à mesure du vieillissement.

En séquençant le génome complet de l’ADN de 560 tumeurs du sein provenant de plusieurs pays, les chercheurs ont identifié plus de 1.600 anomalies suspectées d’être à l’origine des tumeurs. Les anomalies portent sur 93 gènes différents, dont 10 sont altérés dans plus de la moitié des tumeurs du sein.

Certaines de ces altérations étaient déjà connues tandis que d’autres ont été identifiées pour la première fois grâce au séquençage entier du génome qui a permis d’étudier 100% des gènes, alors que jusqu’alors les anomalies connues n’avaient été identifiées qu’au niveau de 10% des gènes.

Cinq nouveaux gènes impliqués dans les cancers du sein ont ainsi été découverts grâce à cet énorme travail mené dans le cadre du consortium international de génomique du cancer (ICGC) mis en place en 2008.

« Ces gènes n’étaient pas jusque-là associés aux cancers du sein », note Mme Chomienne qui espère que cette découverte permettra de trouver de nouveaux traitements ciblés.

« Il est crucial de trouver ces mutations pour comprendre les causes du cancer et développer de nouvelles thérapies », souligne de son côté le Pr Mike Stratton, du Sanger Institute.

Des traitements ciblés existent d’ores et déjà, comme l’Herceptin (trastuzumab) qui permet de cibler des mutations qu’on retrouve dans 15 à 20% des cancers du sein avec métastases.

Selon la directrice d’InCA, l’étude a également permis de trouver des mutations proches des mutations BRCA1 et BRCA2 qui sont présentes dans certains cancers du sein familiaux.

« Les traitements déjà proposés à ces patientes pourraient également s’avérer efficaces chez celles possédant des mutations proches », estime-t-elle.

COFFEE le projet national structurel qui concerne l’Algérie

L’acronyme COFFEE signifie Co-construction d’une Offre de Formation à Finalité d’Employabilité Elevée. COFFEE est un projet structurel national, financé par le programme Erasmus+ Capacity Building, pour une durée de 3 ans à partir d’Octobre 2015. Il est piloté par l’Université de Montpellier.

COFFEE est un projet national structurel qui concerne l’Algérie. Le consortium implique neuf universités, le ministère de l’éducation supérieur et de la recherche scientifique, trois représentants du monde socio-économique (deux algériens et un européen), ainsi que cinq partenaires universitaires européens.

L’objectif premier du projet est de proposer une structure et une méthodologie permettant de créer en Algérie des licences professionnalisantes visant une forte employabilité des diplômés. Les objectifs induits sont de :

- renforcer la coopération au niveau national entre les représentants du monde socio-économique et les représentants du monde universitaire,

- améliorer l’image de marque des licences professionnalisantes

Les objectifs opérationnels du projet se traduisent par :

- une matrice structurelle définissant un cadre pour la création de licences pilotes,

- une procédure de co-construction de ces licences pilotes,

- une plateforme collaborative d’après projet qui permettra la poursuite de la démarche COFFEE pour la création de nouvelles licences professionnalisantes,

- un répertoire des formations, compétences et métiers permettant de mettre en visibilité la relation entre diplômes, compétences et emplois,

- un réseau de spécialistes formés à l’APC (Approche par Compétences) pour la définition des licences,

- dix-huit licences pilotes.

The black-hole collision that reshaped physics

A momentous signal from space has confirmed decades of theorizing on black holes — and launched a new era of gravitational-wave astronomy.

Article tools

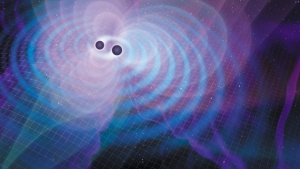

Illustration by Mark Garlick

Binary black holes radiate a huge amount of orbital energy as gravitational waves.

The event was catastrophic on a cosmic scale — a merger of black holes that violently shook the surrounding fabric of space and time, and sent a blast of space-time vibrations known as gravitational waves rippling across the Universe at the speed of light.

But it was the kind of calamity that physicists on Earth had been waiting for. On 14 September, when those ripples swept across the freshly upgraded Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (Advanced LIGO), they showed up as spikes in the readings from its two L-shaped detectors in Louisiana and Washington state. For the first time ever, scientists had recorded a gravitational-wave signal.

“There it was!” says LIGO team member Daniel Holz, an astrophysicist at the University of Chicago in Illinois. “And it was so strong, and so beautiful, in both detectors.” Although the shape of the signal looked familiar from the theory, Holz says, “it's completely different when you see something in the data. It's this transcendent moment”.

The signal, formally designated GW150914 after the date of its occurrence and informally known to its discoverers as 'the Event', has justly been hailed as a milestone in physics. It has provided a wealth of evidence for Albert Einstein's century-old general theory of relativity, which holds that mass and energy can warp space-time, and that gravity is the result of such warping. Stuart Shapiro, a specialist in computer simulations of relativity at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, calls it “the most significant confirmation of the general theory of relativity since its inception”.

But the Event also marks the start of a long-promised era of gravitational-wave astronomy. Detailed analysis of the signal has already yielded insights into the nature of the black holes that merged, and how they formed. With more events such as these — the LIGO team is analysing several other candidate events captured during the detectors' four-month run, which ended in January — researchers will be able to classify and understand the origins of black holes, just as they are doing with stars.

Still more events should appear starting in September, when Advanced LIGO is scheduled to begin joint observations with its European counterpart, the Franco–Italian-led Advanced Virgo facility near Pisa, Italy. (The two collaborations already pool data and publish papers together.) This detector will not only contribute crucial details to events, but could also help astronomers to make cosmological-distance measurements more accurately than before.

“It's going to be a really good ride for the next few years,” says Bruce Allen, managing director of the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Hanover, Germany.

“The more black holes they see whacking into each other, the more fun it will be,” says Roger Penrose, a theoretical physicist and mathematician at the University of Oxford, UK, whose work in the 1960s helped to lay the foundation for the theory of the objects. “Suddenly, we have a new way of looking at the Universe.”

A matter of energy

Physicists have known for decades that every pair of orbiting bodies is a source of gravitational waves. With each revolution, according to Einstein's equations, the waves will carry away a tiny fraction of their orbital energy. This will cause the objects to move a bit closer together and orbit a little faster. For familiar pairs, such as the Moon and Earth, such energy loss is imperceptible even on timescales of billions of years.

But dense objects in very close orbits can lose energy much more quickly. In 1974, radio astronomers Russell Hulse and Joseph Taylor, then of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, found just such a system: a pair of dense neutron stars in orbit around each other. As the years went by, the scientists found that this 'binary pulsar' was losing energy and spiralling inwards exactly as predicted by Einstein's theory.

The two black holes detected by LIGO had probably been losing energy in this way for millions, if not billions, of years before they reached the end. But LIGO did not register the gravitational waves coming from them until 9:50:45 Coordinated Universal Time on 14 September, when the wave's frequency rose above some 30 cycles per second (hertz) — corresponding to 15 full black-hole orbits per second — and was finally high enough for the detectors to distinguish it from background noise.

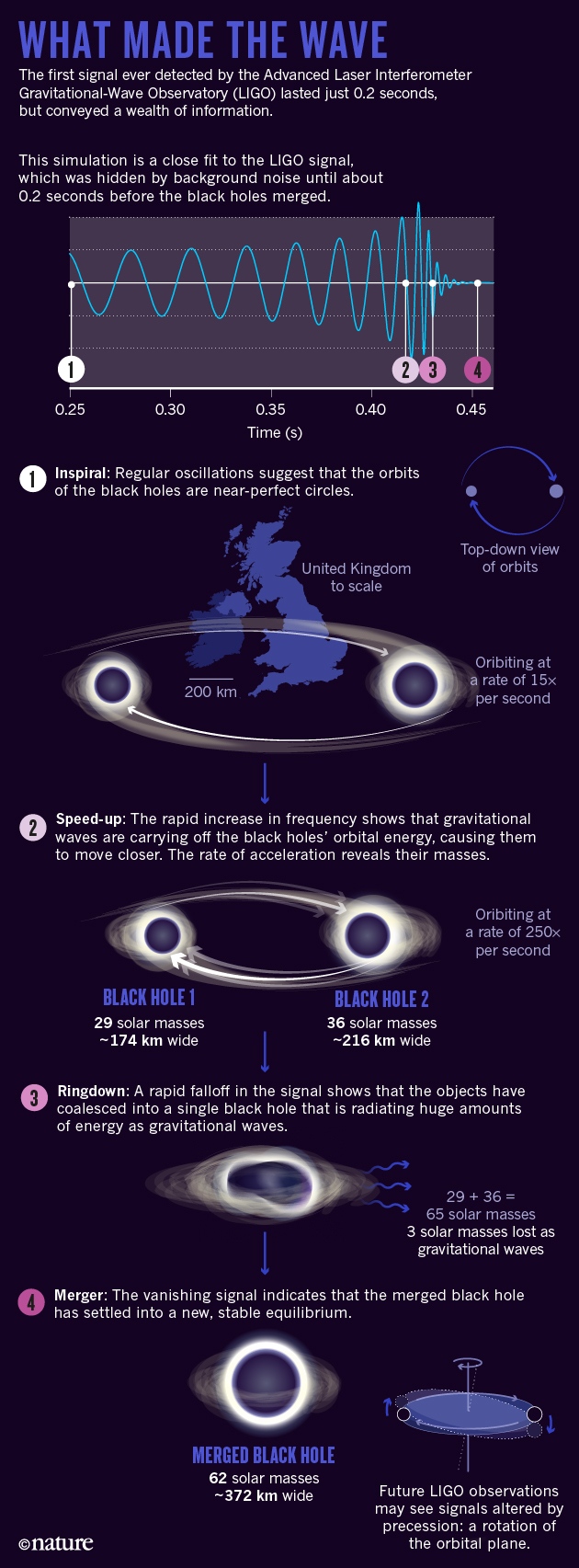

But then, in just 0.2 seconds, LIGO watched the signal surge to 250 hertz and suddenly disappear, as the black holes made their final 5 orbits, reached orbital velocities of half the speed of light and coalesced into a single massive object (see 'What made the wave').

Source: Ref. [1]/Nik Spencer/Nature

The LIGO and Virgo teams soon went to work extracting every bit of information possible. At the most fundamental level, the signal gave them an existence proof: the fact that the objects came so close to each other before merging meant that they had to be black holes, because ordinary stars would need to be much bigger. “It is, I think, the clearest indication that black holes are really there,” says Penrose.

The signal also provided researchers with the first empirical test of general relativity beyond regions — including the space around the binary pulsar — where there is comparatively little space-time warping. There was no empirical evidence that the theory would keep its validity at the extreme energies of merging black holes, says Shapiro — but it did.

The signal held a trove of more-detailed information as well. By scrutinizing its shape just before the final cataclysm, the scientists found that it closely approximated a simple sine wave with a steadily increasing frequency and amplitude. According to B. S. Sathyaprakash, a theoretical physicist at Cardiff University, UK, and a senior LIGO researcher, this pattern suggests that the orbits of the black holes were nearly circular, and that LIGO probably had a bird's-eye view of the circles, looking almost straight down on them rather than edge-on.

In addition, the LIGO and Virgo teams were able to use the frequency of the observed wave, along with its rate of acceleration, to estimate the masses of the two black holes: because heavier objects radiate energy in the form of gravitational waves at a faster rate than do lighter objects, their pitch rises more quickly.

By recreating the Event with computer simulations, the scientists calculated that the two black holes weighed about 36 times and 29 times the mass of the Sun, respectively, and that the combined black hole weighed about 62 solar masses1. The lost difference, about three Suns' worth, was dispersed as gravitational radiation — much of it during what physicists call the 'ringdown' phase, when the merged black hole was settling into a spherical shape. (For comparison, the most powerful thermonuclear bomb ever detonated converted only about 2 kilograms of matter into energy — roughly 1030 times less.) The teams also suspect that the final black hole was spinning at perhaps 100 revolutions per second, although the margin of error on that estimate is large.

The inferred masses of the two black holes are also revealing. Each object was presumably the remnant of a very massive star, with the larger star approaching 100 times the mass of the Sun and the smaller one a little less. Thermonuclear reactions are known to convert hydrogen in the cores of such stars into helium much faster than in lighter stars, which leads them to collapse under their own weight only a few million years after they are born. The energy released by this collapse causes an explosion called a type II supernova, which leaves behind a residual core that turns into a neutron star or, if it's massive enough, a black hole.

Scientists say that type II supernovae should not produce black holes much bigger than about 30 solar masses — and both black holes were at the high end of that range. This could mean that the system formed from interstellar gas clouds that were richer in hydrogen and helium than the ones typically found in our Galaxy, and that were poorer in heavy elements — which astronomers call metals.

Astrophysicists have calculated that stars formed from such low-metallicity clouds should have an easier time forming massive black holes when they explode, explains Gijs Nelemans, an astronomer at Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands and a member of the Advanced Virgo collaboration. That's because during a supernova explosion, smaller atoms are less likely to be blown away by the blast. Low-metallicity stars thus “lose less mass, so more of it goes into the black hole, for the same initial mass”, Nelemans says.

Two by two

But how did these two black holes end up in a binary system? In a paper2 published at the same time as the one reporting the discovery, the LIGO and Virgo teams described two commonly accepted scenarios.

The simplest one is that two massive stars were born as a binary-star system, forming from the same interstellar gas cloud like a double-yolked egg, and orbiting each other ever since. (Such binary stars are common in our Galaxy; singletons such as the Sun are the exception, rather than the rule.) After a few million years, one of the stars would have burned out and gone supernova, soon to be followed by the other. The result would be a binary black hole.

The second scenario is that the stars formed independently, but still inside the same dense stellar cluster — perhaps one similar to the globular clusters that orbit the Milky Way. In such a cluster, massive stars would sink towards the centre and, through complex interactions with lighter stars, form binary systems, possibly long after their transformation into black holes.

“It is, I think, the clearest indication that black holes are really there.”

Simulations made by Simon Portegies Zwart, an astrophysicist at Leiden University in the Netherlands, show3 that massive stars are more likely to form in dense clusters, where collisions and mergers are more common. He also finds that once a binary black-hole system forms, the complex dynamics of the cluster's centre would probably kick the pair out at high speed. The binary that Advanced LIGO detected may have wandered away from any galaxy for billions of years before merging, he says.

Although the LIGO and Virgo teams were able to learn a lot from the Event, there is much more that gravitational waves could teach them, even in the case of black-hole mergers.The detectors showed that immediately after the black holes merged, the waves quickly died down as the resulting black hole settled into a symmetrical shape. This is consistent with predictions made by theoretical physicist C. V. Vishveshwara in the early 1970s, a time when “gravitational waves and black holes both belonged to the realm of mythology”, he says. “At that time, I had not imagined that it would ever be verified,” says Vishveshwara, who is director emeritus of the Jawaharlal Nehru Planetarium in Bangalore, India.

But LIGO saw only just over one cycle of the Event's ringdown waves before the signal became buried once more in the background noise — not yet enough data to provide a rigorous test of Vishveshwara's predictions.

More-stringent tests will be possible if and when LIGO detects black-hole mergers that are larger than this one, or that occur closer to Earth than the Event's estimated distance of 1.3 billion light years, and thus give 'louder' waves that stay above the noise for longer.

Alessandra Buonanno, a LIGO theorist and director of the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Potsdam-Golm, Germany, says that a more detailed picture of the ringdown stage could reveal how fast the final black hole rotates, as well as whether its formation gave it a 'natal kick', imparting a high velocity.

In addition, says Sathyaprakash, “we are especially waiting for systems that are much lighter, so they last longer”. Such events could include the mergers of lighter binary black holes, of binary neutron stars or of a black hole with a neutron star. Each type would deliver its own signature chirp, and could produce a signal that stays above LIGO's threshold of sensitivity for several minutes or more.

“GW150914 is in some sense a very vanilla system,” says Chad Hanna, a LIGO member at Pennsylvania State University in University Park. “It's beautiful, of course, but it doesn't have all the crazy things that one might expect.”

Space artistry

One phenomenon that Sathyaprakash is eager to observe is a 'precession' of the black holes' orbital plane, meaning that their paths trace a kind of 3D rosette. This is a relativistic effect that has no counterpart in Newtonian gravity, and it should produce a characteristic fluctuation in the strength of the gravitational waves. But orbital precession occurs only when two black holes have axes of rotation that point in random directions, and it disappears when the axes are both perpendicular to the orbital plane. The occurrence of a precession could provide clues to how the black holes formed.

It's hard to be sure about that possibility because there are many uncertainties in simulating supernovas. But astrophysicists suspect that parallel spins generally signify that the original two stars were born together out of the same whirling gas cloud. Similarly, they think that random spins result from black holes that formed separately and later fell into orbit around each other. Once the observatories find more mergers, they may be able to determine which type of system occurs more frequently.

Although detecting more events will help LIGO to do lots of science, its interferometers have intrinsic limitations that make it necessary to work together with a worldwide network of similar detectors that are now coming online.

First, LIGO's two interferometers are not enough for scientists to determine precisely where the waves came from. The researchers can get some information by comparing the signal's time of arrival at each detector: the difference enables them to calculate the wave's direction relative to an imaginary line drawn between the two. But in the case of the Event, which recorded a difference of 6.9 milliseconds, their calculations limited the field of possibilities merely to a wide strip of southern sky.

Had Virgo been online, the scientists could have narrowed down the direction substantially by comparing the waves' arrival times at three places. With a fourth interferometer (Japan is building an underground one called KAGRA, for Kamioka Gravitational-Wave Detector, and India has its own LIGO in planning), their precision would improve much more.

Knowing an event's direction will in turn remove one of the biggest uncertainties in determining its distance from Earth. Waves that approach from a direction exactly perpendicular to the detector — either from above or from below, through Earth — will be recorded at their actual amplitude, explains Fulvio Ricci, a physicist at the University of Rome La Sapienza and the spokesperson for Virgo. Waves that come from elsewhere in the sky, however, will hit the detector at an angle and produce a somewhat smaller signal, according to a known formula. There are even some blind spots, where a source cannot be seen by a given detector at all.

Determining the direction will therefore reveal the exact amplitude of the waves. By comparing that figure with the waves' amplitude at the source, which the researchers can derive from the shape of the signal, and by knowing how the amplitude decreases with distance, which they get from Einstein's theory, they can then calculate the distance of the source to a much higher precision.

This situation is almost unprecedented: conventionally, astronomical distances need to be estimated by looking at the brightness of known objects in locations that range from the Solar System to distant galaxies. But the measured brightness of those 'standard candles' can be dimmed by stuff in between. Gravitational waves have no such limitation.

Raising the alarm

There is another important reason why scientists are eager to have precise estimates of the waves' provenance. The LIGO and Virgo teams have arranged to give near-real-time alerts of intriguing events to more than 70 teams of conventional astronomers, who will use their optical, radio and space-based telescopes to see whether those events produced any form of electromagnetic radiation. In return, the LIGO and Virgo collaborations will be sifting through data to search for gravitational waves that could have been generated by events, such as supernova explosions, seen by the conventional observatories.

Some 20 teams tried to follow up on the Event, mostly to no avail. NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope did see a possible burst of γ-rays about 0.4 seconds later, coming from an equally vague but compatible region of the southern sky4. But most observers now consider it to be a coincidence. Such γ-rays could, in principle, have been produced when gas orbiting the binary black hole was heated up during the merger, says Vicky Kalogera, a LIGO astrophysicist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. But “our astrophysical expectation has been that the gas from stars that formed the binary black hole has long dispersed. There shouldn't be any significant gas around”, she says.

Going forward, however, matching gravitational waves with electromagnetic ones could usher in a new era of astronomy. In particular, mergers of neutron stars are expected to produce short γ-ray bursts. Researchers could then measure how far the light from those bursts is shifted towards the red end of the spectrum, which would tell astronomers how fast the stars' host galaxies are receding owing to the expansion of the Universe.

Matching those redshifts to distance measurements calculated from gravitational waves should give estimates of the current rate of cosmic expansion, known as the Hubble constant, that are independent — and potentially more precise — than calculations using current methods. “From the point of view of measuring the Hubble constant, that's our gold-plated source”, says Holz.

The LIGO and Virgo teams estimate that they have a 90% chance of finding more events in the data that LIGO has already collected. They are confident that by the time the next run finishes, the event count will be at least 5, growing to perhaps 35 by the end of a run scheduled to start in 2017.

“To be honest,” says Holz, “I find it really hard to believe that the Universe is really doing this stuff. But it's not science fiction. It really happened.”

Plateforme des biotechnologies végétales aux services de la formation, la recherche et la création d’entreprises

Cette plateforme réalisée dans le cadre des activités du laboratoire de génétique, biochimie et biotechnologies végétales est dédiée à traiter des thématiques suivantes

- La génomique végétale

- Amélioration des plantes

- Biodiversité végétale

- Cytogénétique

plateforme biotechnologies végétales.PDF

Geoscience: Ups and downs

Unsettled markets lead to shifting employment prospects for petroleum geoscientists.

Steep declines in oil prices have decimated oil companies' profits and squeezed a once-booming demand for petroleum geoscientists. In a one-two punch, the price of oil plunged to a 12-year low and energy companies were forced to shed tens of thousands of jobs and slash their oil- and gas-exploration budgets.

The situation is the worst for some time. In January, the price of oil fell to less than US$28 per barrel, down from more than $100 per barrel in 2014 — squashing short-term employment prospects for geologists and geophysicists. Shell, one of the sector's largest companies, has already announced the loss of about 10,000 jobs, and its competitors Chevron and BP have also revealed cuts that number in the thousands. Worldwide, graduate programmes that for decades have been the leading suppliers of talent to energy companies can no longer instantly place their freshly hatched master's-level geoscientists.

Steve Satushek/Getty

A petroleum pipeline at Anacortes, Washington.

“We've had at least a 50% drop in hiring — some major companies are not hiring at all,” says Maurine Riess, director of the geosciences career centre at the University of Texas at Austin, which historically has been a main pipeline for energy-company recruitment. And the master's programme in integrated petroleum geoscience at the University of Aberdeen, UK, another long-time provider, has also felt the impact: last year, one-quarter of its graduates could not immediately get industry jobs. Some of those who were hired elsewhere found roles in risk analysis or finance — fields that are distant from those in which they have trained.

Energy analysts predict a dim outlook for those seeking positions in geoscience for at least the next year (see 'Survival tips for petroleum geoscientists'). But demand for expertise in geology and geophysics is expected to grow in the longer term across the oil and gas industries owing to a pending wave of retirements, a growing demand for technical and leadership skills and a continuing need for oil. Analysts also foresee an increasing demand for this expertise in the environmental sector, notably in impact mitigation — the development and implementation of ways to reduce or eliminate the effects of oil and gas exploration and extraction on the environment.

Energy uncertainty

Instability is not unusual in the energy sector, and this most recent decline in the price of oil is due, very simply, to a glut of oil on the market. Between 2000 and 2008, the price of oil rose sharply and peaked at a record high of almost $150 per barrel. But then a global recession sent the price down to about $40 per barrel by the end of 2008. Although the subsequent economic recovery lifted the price over the next five years, by mid-2014, the price began to drop once more as demand decreased. And at the same time, production has risen in the Middle East, the United States and Canada. These factors have combined to create an unusual excess of oil.

Boom–bust cycles in the sector have produced an uneven workforce demographic that could actually mean good news for early-career geologists over the next five to ten years. The American Geosciences Institute (AGI) in Alexandria, Virginia, a network of associations that represents geoscientists, foresees a shortage of at least 135,000 professionals in the United States by 2022. Its forecast derives in part from the fact that many US geoscientists will soon be at or near retirement age. In academia, for example, the average faculty member in the United States is aged 60. “Half the industry's workforce is retiring in the next several years — with or without the downturn. That's a pretty big human-capacity gap that will have to get filled,” says Christopher Keane, the AGI's director of communications and technology.

And despite the present oversupply, energy companies must still pursue a certain level of oil exploration to remain profitable, says Stephen Barnes, director of the Economics and Policy Research Group at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. Barnes, who tracks the workforce needs of the oil industry, says that the discovery of new oil fields, a chief component of exploratory missions, requires a high level of expertise. Keane says: “The million-dollar question — and we can't answer this because companies hold that info tight — is, how many companies prepare for a rebound ahead of time and staff accordingly?” Barnes adds that when the demand for new recruits ramps up, skilled geoscientists are likely to be sought first because their specialized knowledge will be required for exploratory missions.

Early-career geoscientists should be aware that opportunities in the field will rise and fall with the price of oil. “The only constant in this industry is change, so be comfortable with that,” says Carlos Dengo, director of the Berg-Hughes Center for Petroleum and Sedimentary Systems at Texas A&M University in College Station. Here are some tips for working in the sector.

The pending retirement wave and a closer focus on climate change and environmental issues, notably in the area of mitigation, will open up opportunities for geoscientists. And the environmental implications of oil exploration and extraction will be an important driver of workforce demand in the near future, predicts Carlos Dengo, a former ExxonMobil executive and current director of the Berg-Hughes Center for Petroleum and Sedimentary Systems at Texas A&M University in College Station.

Those who focus on subsurface geology have the expertise to develop climate-change mitigation strategies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS), which aims to trap carbon dioxide underground to reduce atmospheric levels of greenhouse gases. “There is no way the world can meet greenhouse-gas emission goals without CCS,” says Philip Ringrose, a specialist in CO2 storage and petroleum geoscience at Statoil in Trondheim, Norway.

At the moment, no one can pinpoint if or when the demand will ramp up. The cost of CCS — and a lack of clarity over who will pay for and insure projects — has meant that its adoption has been uneven. Last November, the UK government cancelled its £1-billion ($1.4-billion) proposed investment in CCS, but both Norway and Canada have government-funded CCS projects under way. Despite the uncertainty, says Ringrose, research funding for CCS has been increasing worldwide.

While the energy sector is in a downturn, geoscientists can look to other fields, Keane points out. In previous periods of decline, their geospatial skills were in demand from the telecommunications industry for the siting of mobile-phone networks, and their proficiency in quantitative-problem management made them highly sought after by finance companies.

Beyond geoscience

Some energy analysts have questioned whether academia can produce the expertise that industry, governments and the non-profit sector will need over the next decade or so, given the ageing workforce and anticipation that the demand for training will exceed the capacity of existing programmes. The overall proportion of US federal funding that is allocated to academic geoscience research has fallen by half since the 1980s, when it represented 11% of basic-research funding. And any specific increases in funding for geoscience research have gone to the environmental or atmospheric sciences. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that geoscience departments in US and UK universities tend to rely on funding from the oil and gas industries, and that typically dwindles during downturns.

“When I started at Texas A&M 2 years ago, my centre had funding for 11 fellowships that came directly from industry. For 2016, I've got 4,” says Dengo. Up to 100 of the more than 400 geoscience master's programmes in the United States now produce most of the new employees for the oil and gas industries.

According to Dengo, these industries want to stop their pattern of slashing support during downturns, which compromises the interest and training of geoscientists. Some companies are eager to support efforts that combine industry and academic expertise to train PhD students. “We sponsor quite a lot of students and use that programme to find the ones we want to employ,” says Jonathan Craig, senior vice-president for exploration at Eni, an oil and gas company in Milan, Italy. And industry support has facilitated the creation of a training initiative in the United Kingdom. Eleven energy companies have contributed financially to the Natural Environment Research Council Centre for Doctoral Training (CDT) in Oil and Gas, located at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh, UK, where the British Geological Survey is also relocating 160 of its geoscientists.

" Despite the ups and downs of this industry, it is surprising how much geoscience skills remain in demand. "

With an investment of £10 million from the Natural Environment Research Council, industry and 17 universities, the CDT will produce at least 120 PhD graduates by 2021. Students conduct research and receive 20 weeks of training from industry experts who address the use of oil, energy regulation and the environmental impact of oil-related activities, among other topics.

Early-career geoscientists who receive training in these fundamentals could have an edge in the job market. CDT director John Underhill says that many industry executives complain that today's workforce lacks such a knowledge base. Four areas in particular — stratigraphy, structural geology, sedimentology and field geology — need to be bolstered to escape what he calls 'Nintendo' geology, an over-reliance on 3D mapping and visualization techniques.

Beyond a solid foundation in core geology, the most marketable geoscientists will also have strong quantitative and soft skills, which include communication, the ability to work in a team and sensitivity towards other cultures. To that end, Dengo has created three part-time teaching positions at Texas A&M that he will fill with former industry executives who can share their global experience and business acumen, as well as their specific areas of expertise.

The fundamental proficiency of geoscientists, their ability to remotely detect and assess what is happening within Earth, will prove most desirable both to employers in and outside the energy sector. “Despite the ups and downs of this industry, it is surprising how much geoscience skills remain in demand, even during difficult times,” says Ringrose.